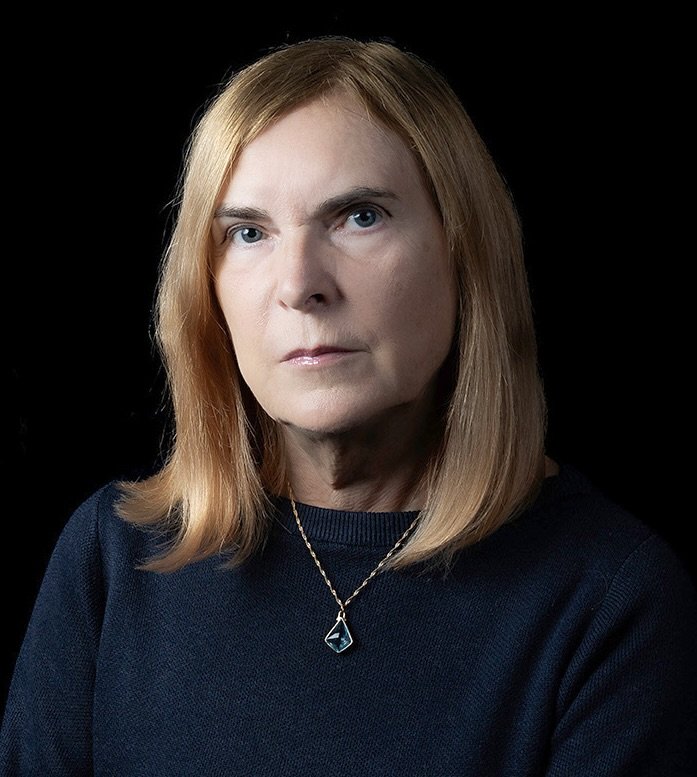

Meet Emöke Andersson Lipcsey

Emöke Andersson Lipcsey

Emöke was born in Budapest and is a Hungarian-Swedish author, translator, journalist, and organist. She has lived in Sweden since 1984. Writing primarily in Hungarian, she often publishes her literary work under the name Emőke Lipcsey.

We had the opportunity to ask Emöke a bit about her creative work which spans the written word, visual poetry, translation and when to choose which medium

You have worked in several creative forms, including poetry, prose, and visual and sound-based work. How do you think these different forms influence one another in your writing life?

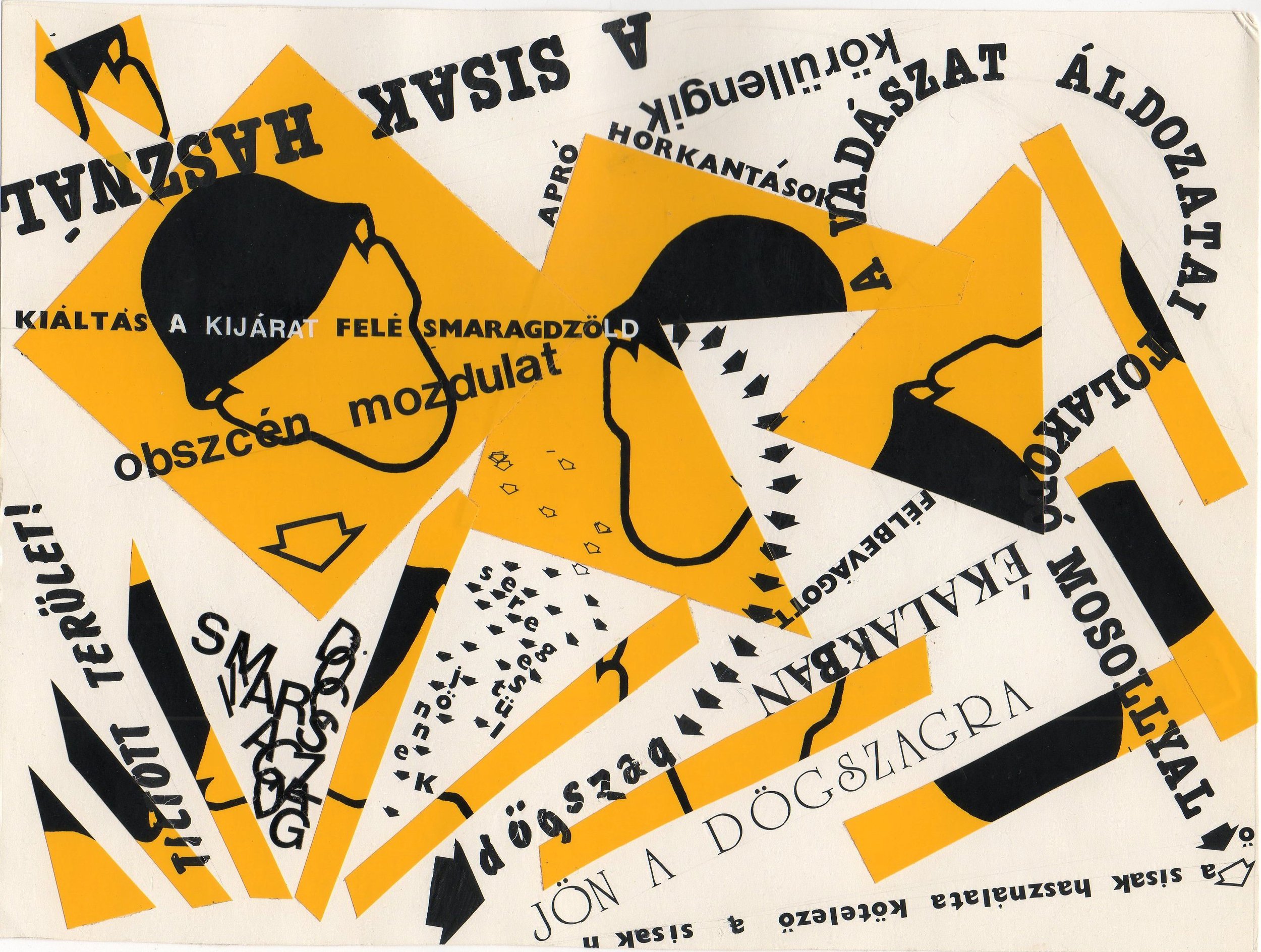

It is not the different forms that influence one another. Behind every form lies the same essence. This essence is composed of so many external and internal factors that it cannot be grasped in itself. A work of art is an event that happens, and through this happening, a fragment of the essence is given a framework, that is, it takes on a form. A visual poem can receive a literal frame so that it may be hung on a wall, but its physical frame may also be nothing more than a page in a book, just like a short story that appears in a volume. A physical frame is unavoidable: without it, the work could not be perceived by others. From the perspective of the artwork, however, it is more important what we think about form, about the work's abstract framework. I hold that every closed form is merely a convention. One must constantly experiment with forms so that the work does not run up against limitations and so that it may appear in the form in which it feels at home. Forms can also be combined; this is how, for example, the sound-image poem comes into being, a poem that simultaneously contains both visual and musical elements.

Your background spans Hungary, France, and Sweden. How have these different environments shaped your voice as a writer?

Every new environment adds something to a person's personality, or takes something away from it. My Hungarian roots, my studies in France, and the years I spent in Sweden have all been stored within me. I constantly draw from this reservoir of experiences, lived moments, languages, and often sharply different ways of thinking. The development of a writer's voice, however, is not, in my view, dependent on environment. The environment shapes what I write about and the raw material I draw from, but it does not influence the tone of my writing.

You have spent time both creating original work and translating the work of others. What has translation taught you about writing and about language itself?

In the course of their work, translators learn an enormous amount about language, about language in general, and especially about the two languages between which a work is transferred. Thomas Tranströmer, the Swedish Nobel Prize–winning poet, never actually spoke of translation. He called it interpretation when he "translated" the works of others into Swedish. He was right. The logic, structure, and sheer extent of the vocabulary of different languages are often so radically different that transferring a work into another language is at least as great a challenge as trying to plant a rose on the Moon. This is particularly true, for example, of Hungarian and Swedish. I generally translate from Swedish into Hungarian, and with every sentence I am confronted with how fundamentally different the operating principles of the two languages are. In this connection, let me share an anecdote. Enrico Fermi, the Italian nuclear physicist who worked with many Hungarian scientists and was amazed by their language and way of thinking, was once asked whether he believed in extraterrestrials. He replied: yes, they are already among us. They are called Hungarians.

Your book Haren gör en kullerbytta experiments with storytelling and structure. What drew you toward this kind of exploration?

Haren gör en kullerbytta (The Wild Hare Turns a Somersault), the Taurus Blog, and my novel Ördöghinta (The Devil's Carousel) are all experiments. My short stories, my poems, and my visual poems are experiments as well, experiments all of them. I experiment with form, language, and medium, and I encourage the reader to take a more active role in interpreting the work. Why? Because in literature, just as in the natural sciences, only continuous experimentation can bring something new into being.

In my laboratory, for example, I placed the novel Ördöghinta within three interwoven timelines that act upon one another in every direction, while the narrative of Taurus Blog takes the form of a blog. In Haren gör en kullerbytta, two worlds are intertwined: the rational and tangible, and that which lies beyond them. I believe that time is not linear, but that past, present, and future exist simultaneously; only human beings are incapable of perceiving this. At the same time, there are many realities (including virtual reality); existence unfolds across multiple planes, not solely on the one where we live out our lives along the line of linear time. This paradox in itself compels me to experiment, because I am curious about what lies behind the perceivable. In my experimental spirit, I also try out different media. When creating my visual poems, for instance, I use everything from photocopiers to various computer programs, whatever happens to be at hand. Recently, artificial intelligence has also entered my field of vision.

When an idea first comes to you, how do you know if it belongs on the page, in a visual or sound-based format, or somewhere in between?

You can never know this in advance. There is an idea, a sentence fragment, a problem that preoccupies me, an image, a snippet of sound. I capture it, I note it down. At the same time, I have plans: to write a novel with roughly this or that theme, or to create a visual poem, or perhaps, upon commission, a text on a given topic. Then I turn to my repository of ideas, leaf through it, and select those that resonate with my plans.

Music is an important part of your life. In what ways does your work as a musician influence the way you think about rhythm, movement, or shape on the page?

Music has an enormous influence on the way I think. I could say that all my cognitive functions are fundamentally musical in origin. As a concert organist, I played a great many works by J. S. Bach. The logic, language, and structure of Bach's music, in which everything is connected to everything else, have profoundly shaped my thinking, even though I am not actively making music these days. The imprint of Bach's music is present in everything I do.

Looking back at your career so far, is there a moment or project that feels especially meaningful to you?

I am not only a writer but also a human being. There have been many important, defining moments and projects in my life so far, but the one I would single out is the moment when my son was born.

What are you working on now that excites you?

I am interested in the philosophical and existential dimensions of artificial intelligence. I am writing a series of essays on this topic, and in the same spirit, a novel is also taking shape in which ancient Greek mythology and the emergence of artificial intelligence intertwine. In the spring, a new collection of short stories will be published, in which several stories likewise revolve around questions of AI and simulated reality. I have also accumulated enough poems and visual poems that I am planning to put together a poetry volume as well.

Many writers in our community work across cultures or languages. What advice would you offer to someone trying to find their creative footing in more than one literary world?

One must keep experimenting with genres and forms until it becomes clear which one feels like home. At the same time, there is no need to remain confined to a single genre or mode of expression, since for the creator, the experiment itself, the path, is more important than the work itself.

If you could imagine a conversation between yourself and any writer or artist, living or not, who would you choose and what would you most like to talk about?

That is a difficult question. I wouldn't be able to choose just one artist. I would gladly talk with Johann Sebastian Bach about music and everyday matters as well, about anything, really, in order to get to know his way of thinking more closely. With Miklós Erdély, the Hungarian conceptual artist, polymath, and philosopher, I would continue our conversation about life where we left off. Unfortunately, when he died, I was still too young and too immature for such conversations. Among contemporaries, for example, I would very much like to talk with Kazuo Ishiguro about his novel Klara and the Sun, since it also deals with artificial intelligence and may be the first novel to address the role of AI in a dystopian world.